What do tigers eat? Tigers are one of the biggest cats on the planet. By nature, tigers are carnivores. They eat a good variety of prey depending upon the terrain they live in, ranging from termites to baby rhinos and everything in between. In this article, we’ll explore the tiger hunting pattern and exact diet plan for each tiger type.

Table of Contents

- How Do Tigers Hunt?

- How Much Does A Tiger Eat?

- How Often Do Tigers Eat?

- How Do Tigers Kill Its Prey?

- At What Times Do Tigers Hunt?

- What Do Tigers Eat?

- Do Tigers Eat Humans?

- Tiger Food Chain Diagram

- Tiger Diet By Species

- Tiger’s Mastery Adaptations for Hunting in the Wild

- Tigers’ Diet: Ecological Role and Importance

- Comparison of Tiger Diets with Other Big Cats

- Comparative Dietary Habits

- Seasonal and Habitat-related Variations in Tiger Diet

- Unusual or Surprising Prey of Tigers

- Captive Tiger Diets

- Hunting Success Rates and Strategies of Tigers

- Scavenging Behavior in Tigers

- Cub Dietary Needs and Development of Tigers

- Impact of Climate Change and Conservation Efforts on Tiger Diet

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What do tigers mainly eat?

- How are tigers different from lions when it comes to hunting?

- How much food can tigers eat at one time?

- For tigers mainly, does the size of the prey matter?

- How do the hunting habits of male and female tigers vary?

- Are there tiger subspecies that prefer specific types of prey?

- How has the scarcity of prey affected the tiger population?

- Why are tigers considered efficient hunters?

- Do tigers eat anything other than meat?

- What makes the tiger such a powerful and successful predator?

How Do Tigers Hunt?

Tigers hunt alone rather than in groups. When the tiger cubs are a few months old, the tiger mother involves them in hunting, so they get trained at a very young age. They get proteins from the animal fat. Here are some tiger facts and information on hunting.

- Tigers rely on their sight rather than the smell of the prey. They use their dark striped skin as an effective camouflage to disguise themselves in the hideouts, especially among the long grass, resembling the vertical pattern of light and shade. This allows them to get very close to their prey without being detected before launching an attack.

- Tigers sit for a long time in absolute silence and then pounce on the prey when it is unexpected.

- It is estimated that tigers make at least 20 attempts before killing their prey.

- Tigers furiously run from a complete stand-still position to 50 mph speed in short sprints.

- Hunting sometimes takes its toll on tigers. Tigers could get seriously injured during the process too if the prey attacks them back (such as crocodiles, porcupines or heavy buffaloes).

- Male and female tigers hunt differently. Female tigers hunt only within their territories, while males hunt anywhere and anytime.

![]()

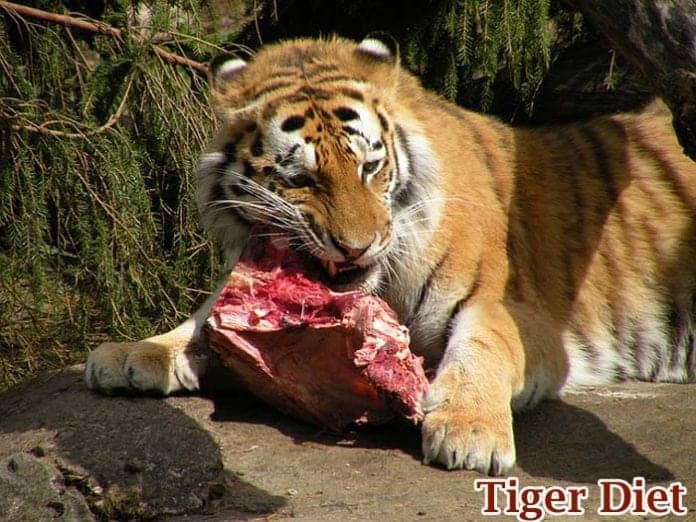

How Much Does A Tiger Eat?

The average weight of tigers is about 700 lbs. They consume about 35-110 lbs of meat at a given time. However, this could vary depending upon what they kill (a large hoofed animal vs. rabbit/rodent).

![]()

How Often Do Tigers Eat?

Typically tigers eat once every two days after feasting on a large mammal. According to the statistics, a tiger kills about one large animal per week, thus about 50 to 52 animals per year.

![]()

How Do Tigers Kill Its Prey?

Tigers use their front claw which has the built-in expand/retract mechanism as needed while grabbing its prey.

- They attack the animal either on the side or from the back so the prey cannot move away quickly. The first powerful bite would be on the neck to break its neck bone and then rip the throat out.

- Once killed, the tiger would drag the dead animal to a secluded area for a peaceful and quiet meal.

- Tiger prey suffers the quickest and least stressful death.

![]()

At What Times Do Tigers Hunt?

If tigers are really hungry and the prey is on sight, they would hunt right away. Generally, tigers prefer hunting on cool or cloudy days. Also, the sunset would be a good time for tigers to go for a kill when the animals wind down after a long day of grazing. Studies show that a tiger’s night vision is six times better than a human’s.

![]()

What Do Tigers Eat?

Being apex predator, what animals do tigers eat? Tigers can eat any moving animals with meat on them. Tiger is not a picky eater. They eat whatever is available.

- It includes all species of deer (sambar, chital (spotted-deer), sika deer, nilgai & more), leopards, gaur, boars, wild pigs, zebras, bears (grizzly or black), tapirs, horses, buffalos, rhino calves, wild dogs, wild cattle, antelopes, young elephants, moose, and goats.

- If a large prey is not available, the tiger will settle for little mammals such as hares, rodents, frogs, snakes, birds, monkeys (such as Langurs), fishes (depending upon location), lizards, or even termites.

- If animals are unavailable, the tiger would eat berries or grass to regulate its digestive system.

![]()

Do Tigers Eat Humans?

Of course! They do.

- There were many incidents in the past where these big cats pounced on humans & killed them for meat. Even these days, we hear horror stories on the news from zoos and in villages where tigers invade due to loss of habitats and in search of food.

- In 1903, Calcutta (now Kolkotta) witnessed the monster man-eater in a zoo that supposedly took more than 200 human lives.

- Even now, the human-tiger conflict continues.

![]()

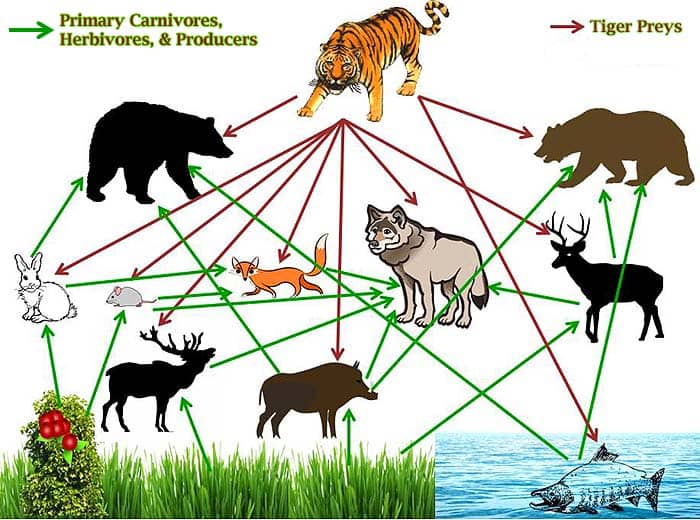

Tiger Food Chain Diagram

- The above diagram shows that the tiger sits at the top of the food chain in the ecosystem with no predators and feeds on the primary carnivores and herbivores directly.

- The second layer represents the primary carnivores, such as foxes and wolves, which feed on the herbivores.

- The third layer represents the herbivores such as deer, elks, and boars, which feed on the producers – vegetation such as trees, berries, and grass.

![]()

Tiger Diet By Species

Each type of tiger has a different diet based on its location. We have tabulated each known tiger species and what they eat in the wild below:

Diet of Siberian Tiger

Siberian tigers also referred as Amur tigers. Now, they are mainly found in the Primorye Province of Russia. Let’s explore what Siberian tigers eat below.

- In the cold terrain, Siberian tigers eat red deer, wild boar, Manchurian elk, and sika deer. Also, tigers attack and eat grizzly bears and black bears.

- Amur tigers are at the top of the food chain in the Siberian ecosystem and have no natural predators.

- However, due to their endangered status and declining population, there is a threat of creating a significant imbalance in the ecosystem where the wolf population could triple in size while the deer/elk species count could decline as well to force them into endangered status.

![]()

South China Tiger Diet

The South China tiger is also called “Chinese Tiger” or “Amoy Tiger”, and it is considered critically endangered by the IUCN.

- They eat serow, tufted deer, sambar deer, muntjac deer, and wild boars. South China tigers can eat around 40-80 lbs of meat at a given time. Being on top of the ecological pyramid, only humans are their predators.

- See why tigers became endangered here.

![]()

Indochinese Tiger Diet

Indochinese tigers are mostly found in Burma, Thailand, Lao PDR, Vietnam, Cambodia and southern China. They are enlisted as endangered by the IUCN.

- Their main diet includes sambar deer, antelope, wild pigs, buffalos, serow, young gaur, baby rhinos, turtles, fishes and baby elephants.

- When food is scarce, Indochinese tigers even go after porcupines, hog badgers (Arctonyx collaris), macaques, monkeys, and muntjac deer.

![]()

Malayan Tiger Diet

Malayan tigers are found in the peninsula of Malay. In 2015, they were officially announced as critically endangered tiger species.

- Malayan tigers’ diet includes deer species (sambar and barking), wild boar, bearded pigs, and serow. Malayan tigers also prey on sun bears (Helarctos malayanus), young elephants, and rhino calves. Due to human encroachment, livestock such as domestic cattle become prey to these tigers.

- Interestingly, Malayan tigers also hunt at night (Nocturnal) to find their prey. As the food chain leader, there is no natural enemy other than humans.

![]()

Sumatran Tiger Diet

In 2008, the IUCN declared that the Sumatran tigers from Sumatran islands and Indonesia as critically endangered species. What do Sumatran tigers eat?

- Sumatran Tigers eat fishes, monkeys, crocodiles, fowl (birds), wild pigs, and deer.

- They are patient hunters and usually stalk the prey for 1/2 hour before attacking. Sumatran tigers have an interesting habit – once the meal is over, they would cover the carcass with grass using their paws to snack on the leftovers later!

![]()

Bengal Tiger Diet

Being the resident of India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan, what do Bengal tigers eat?

- Bengal tigers prefer hunting large mammals such as deer (chital, sambar, gaur, barasingha), water buffalo, nilgai/blue bull, serow (goat-like), and takin (gnu goat).

- On the medium-sized species list, they frequently kill a wild boar, rarely hog deer, muntjac deer, and grey langur (black-faced monkeys).

- When Bengal tigers encounter small prey species such as porcupines, hares, or peafowl, they kill them for snacks.

- Due to humans invading their habitats, Bengal tigers also prey on domestic cattle and get killed by furious people. We hear this news from India very frequently.

![]()

The other three types of tigers, namely the Bali, Javan, and Caspian, are extinct. Their diets were mainly large hoofed mammals.

Tiger’s Mastery Adaptations for Hunting in the Wild

Tigers are among the most proficient hunters in the animal kingdom. Their hunting adaptations have evolved over millennia, enabling them to become apex predators in diverse habitats. These multifaceted adaptations involve physical prowess, sensory acuity, and behavioral strategies that ensure their survival and dominance.

Tigers possess a range of physical adaptations that make them formidable hunters. Their muscular build provides the strength needed to tackle large prey. The structure of a tiger’s limbs, particularly the powerful hind legs, allows for explosive bursts of speed and agility, critical during a chase. Additionally, their retractable claws and sharp teeth are perfectly designed for grasping and killing prey efficiently.

Muscular Strength and Limb Structure

Tigers are known for their powerful build. Their muscular limbs, particularly the hind legs, enable them to leap distances of up to 30 feet in a single bound. This capability is essential for ambushing prey and overcoming obstacles in their environment.

Claws and Teeth

The tiger’s retractable claws are vital for maintaining stealth and sharpness. When not used, the claws are retracted into sheaths, preventing wear and tear.

During an attack, these claws extend to provide a deadly grip on prey. Their canines, which can measure up to 3 inches, are designed to puncture the throats or spinal cords of their prey, ensuring a quick and efficient kill.

Vision

Tigers have excellent night vision, crucial for hunting during dawn and dusk when their prey is most active. Their retinas contain a high concentration of rod cells, enhancing their ability to see in low-light conditions. This adaptation gives them a significant advantage over their prey, which they may not see as well in the dark.

Hearing and Smell

A tiger’s hearing is acute, capable of detecting inaudible sounds in humans. They can pick up the slightest rustle in the underbrush, alerting them to the presence of potential prey.

Their sense of smell is equally impressive, allowing them to track animals over long distances and even detect the pheromones of other tigers.

Suggested Reading:

Top 16 Animals with the Best Hearing

Solitary Hunting

Tigers are solitary hunters, unlike other big cats that may hunt in groups. This behavior reduces competition for food and allows them to cover larger territories. Solitary hunting also means that tigers rely on stealth and surprise rather than the brute force of a group attack.

Ambush Tactics

Tigers are masterful ambush predators. They use the cover of vegetation to approach their prey silently. Once within striking distance, they launch a rapid, powerful attack, often aiming for the neck or throat to subdue their prey quickly. This method of hunting is highly effective and minimizes the risk of injury to the tiger.

![]()

Tigers’ Diet: Ecological Role and Importance

Tigers play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of their ecosystems. As apex predators, they help control the populations of herbivores, preventing overgrazing and promoting biodiversity. Their presence is an indicator of a healthy, functioning ecosystem.

Controlling Herbivore Populations

By preying on large herbivores such as deer and wild boar, tigers help to keep these populations in check. This predation pressure prevents overgrazing, which can lead to habitat degradation and loss of plant species. This balance supports the ecosystem’s overall health and ensures resource availability for other species.

Promoting Biodiversity

The presence of tigers can promote biodiversity in their habitats. Regulating prey populations creates opportunities for various plant and animal species to thrive. This biodiversity is essential for the resilience and sustainability of ecosystems, particularly in the face of environmental changes and human impacts.

Trophic Cascade

Removing tigers from an ecosystem can lead to a trophic cascade, where the populations of prey species increase unchecked, leading to overgrazing and habitat destruction. This can result in the decline of other species and a reduction in biodiversity.

Tigers help maintain a balance by keeping herbivore populations in check, which protects vegetation and supports a healthy ecosystem.

Human-Tiger Interactions

The relationship between humans and tigers is complex, with positive and negative interactions influencing conservation efforts and local economies.

Ecological Benefits to Farmers

In regions like the eastern Himalayas, the presence of tigers has been found to reduce crop and livestock losses. This is because tigers help control the populations of herbivores that would otherwise damage crops. Thus, tigers indirectly support agricultural productivity and local livelihoods.

Conservation and Livelihoods

The presence of tigers can also boost ecotourism, providing economic benefits to local communities. Effective conservation strategies that involve local populations can lead to sustainable livelihoods while protecting tiger habitats.

Case Study: Sumatran Tigers

In Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, research has shown that the abundance of tigers and their prey is significantly influenced by human activities such as hunting and habitat loss.

In areas with low human population density, tiger and prey populations were significantly higher, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts to reduce human impact and protect these vital predators.

Comparison of Tiger Diets with Other Big Cats

Tigers are one of the animal kingdom’s largest and most powerful predators. Understanding their diet and comparing it with other big cats provides insight into their ecological roles and strategies to thrive in their environments.

This section explores the dietary habits of tigers. It compares them with those of other big cats like leopards, lions, and cheetahs, highlighting the unique adaptations and prey preferences that differentiate these magnificent predators.

![]()

Comparative Dietary Habits

Tigers vs. Leopards

Tigers and leopards often share habitats, but their dietary preferences help reduce competition. Tigers typically prey on larger animals, while leopards hunt smaller prey like deer and monkeys.

A study in the Bandipur Tiger Reserve, India, found that while both tigers and leopards hunt chital deer, tigers also consume larger prey like gaur, which leopards generally avoid due to the risk and their smaller size.

| Tiger | Sambar, Wild Boar, Chital | 60-250 kg | Large (60-250 kg) |

| Leopard | Chital, Langur, Small Deer | 20-70 kg | Medium (20-70 kg) |

![]()

Tigers vs. Lions

Lions, unlike tigers, often hunt in groups, allowing them to take down very large prey such as buffalo and giraffes. This social hunting strategy enables lions to target a broader range of large prey compared to the solitary hunting strategies of tigers.

However, both tigers and lions prefer medium to large ungulates, although lions in pride can tackle prey that would be too dangerous for a lone tiger.

| Tiger | Sambar, Wild Boar, Chital | Solitary | Large (60-250 kg) |

| Lion | Buffalo, zebra, Wildebeest | Group (prides) | Very Large (100-300 kg) |

![]()

Tigers vs. Cheetahs

Cheetahs specialize in speed and typically hunt smaller and faster prey like gazelles. Unlike tigers, which rely on strength and stealth, cheetahs use their incredible acceleration to outrun prey. This difference in hunting strategy is reflected in their diet, with cheetahs consuming smaller, fleet-footed animals that are less accessible to tigers.

| Tiger | Sambar, Wild Boar, Chital | Ambush | Large (60-250 kg) |

| Cheetah | Gazelles, Impalas | High-speed pursuit | Small to Medium (20-60 kg) |

![]()

Regional Variations

Tigers’ diets can vary significantly depending on their habitat. For instance, the diet of Amur tigers in the Russian Far East heavily relies on wild boar and deer species. In contrast, Bengal tigers in India and Nepal primarily consume different species of deer and wild pigs.

![]()

Tigers, being apex predators, exhibit remarkable adaptability in their dietary habits to cope with seasonal changes and different habitats. Their diet varies significantly depending on prey availability, environmental conditions, and competition with other predators. This section explores how tigers adjust their feeding patterns seasonally and across various habitats.

Seasonal Variations in Diet

Seasonal changes significantly impact the availability of prey, leading to variations in the diet of tigers. During different seasons, tigers adapt by targeting different prey species that are more abundant or easier to hunt at that time.

Winter vs. Summer Diets

Amur tigers have distinct seasonal dietary patterns in colder regions like the Russian Far East. In winter, these animals become the primary diet when prey such as wild boar and deer are more concentrated and easier to locate due to snow cover. Conversely, during summer, the prey base becomes more diverse as animals disperse, and tigers may include smaller mammals and birds in their diet.

| Winter | Wild boar, Sika deer | Roe deer, small mammals |

| Summer | Diverse ungulates | Birds, small mammals, fish |

![]()

Dry vs. Wet Seasons

In tropical regions, such as the Indian subcontinent, the diet of tigers also changes between the dry and wet seasons. During the dry season, water sources are limited, and prey animals tend to congregate around these areas, making them easier targets for tigers.

In contrast, during the wet season, prey dispersion due to abundant water sources results in tigers needing to cover larger areas to find food.

Habitat-Related Variations

A tiger’s habitat influences its diet due to differences in prey availability, vegetation cover, and human presence. Tigers inhabit various environments, from dense tropical forests to open grasslands and mangrove swamps.

![]()

Forested Habitats

Tigers in dense forests, such as those in India and Nepal, primarily prey on large ungulates like sambar deer and chital. The dense vegetation provides cover for ambush hunting, a key strategy for tigers in these areas.

Grasslands and Savannas

In more open habitats, such as the grasslands and savannas of Central India, tigers adapt their hunting strategies to account for less cover. They often hunt during dawn or dusk when visibility for prey is lower. Prey species in these areas include wild boar, buffalo, and deer.

![]()

Mangrove Swamps

The Sundarbans mangrove forest presents a unique habitat where tigers primarily prey on species like spotted deer and occasionally fish and crabs. The challenging terrain of the mangroves requires tigers to be adept swimmers, and their diet here reflects the availability of prey in this aquatic environment.

![]()

Adaptive Strategies

Tigers exhibit a high degree of adaptability in their feeding strategies. During periods of prey scarcity, they may travel greater distances or shift their diet to include less preferred prey, such as smaller mammals or birds. This flexibility is crucial for their survival in diverse and changing environments.

Case Study: Amur Tigers in Northeast China

A study on Amur tigers in Northeast China revealed that wild boar had the highest annual and seasonal consumption frequencies. The seasonal variation showed that tigers adapted their diet based on prey availability, with roe deer and sika deer being more frequently preyed upon in certain seasons.

![]()

Unusual or Surprising Prey of Tigers

Tigers, known for their preference for large ungulates, have occasionally been documented preying on unexpected or unusual animals. These instances provide intriguing insights into these apex predators’ adaptability and opportunistic feeding behavior. Below, we explore some surprising prey choices of tigers, supported by research findings.

Predation on Primates

While tigers typically hunt large herbivores, there have been instances where they have preyed on primates. For example, in the forests of India, common langurs (Presbytis entellus) have been documented as part of the tiger’s diet.

Although these primates are not a primary food source, tigers occasionally hunt them, especially in regions where their preferred prey is scarce.

Consuming Small Mammals and Birds

Tigers have been known to target smaller mammals and birds without larger prey. Studies in the Sundarbans, a unique mangrove habitat, revealed that tigers occasionally prey on birds like pheasants and smaller mammals such as rodents and even monkeys. These findings highlight the tiger’s ability to adapt its hunting strategy based on prey availability.

Predation on Domestic Animals

Tigers living near human settlements sometimes prey on domestic livestock, including cattle, goats, and dogs. This behavior is often a result of habitat encroachment and depletion of wild prey. A study in the Russian Far East noted that Amur tigers preyed on domestic animals when wild prey was scarce, illustrating the tiger’s opportunistic hunting behavior.

Aquatic Prey

In some regions, tigers have been observed preying on aquatic animals. In the Sundarbans, for example, tigers have been known to catch fish and crabs. This behavior is particularly noteworthy given the tigers’ adaptations for hunting on land. The unique environment of the Sundarbans, with its vast network of waterways, necessitates such dietary flexibility.

Scavenging Behavior

Although primarily hunters, tigers are also known to scavenge. Instances of tigers consuming carcasses of animals killed by other predators or those that died naturally have been documented. This scavenging behavior helps tigers conserve energy and still obtain the necessary nutrients.

Predation on Other Predators

In rare instances, tigers have been documented preying on other predators. An Amur tiger preying on a lynx in the Russian Far East is a notable case. Such events are rare and typically occur when the tiger desperately needs food or defending its territory.

Case Study: Sumatran Tigers

A study on Sumatran tigers in Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park revealed a diverse diet that included large ungulates and smaller mammals like mouse deer (Tragulus spp. ) and pigs (Sus scrofa). The presence of such diverse prey highlights the adaptability of Sumatran tigers to varying prey availability.

![]()

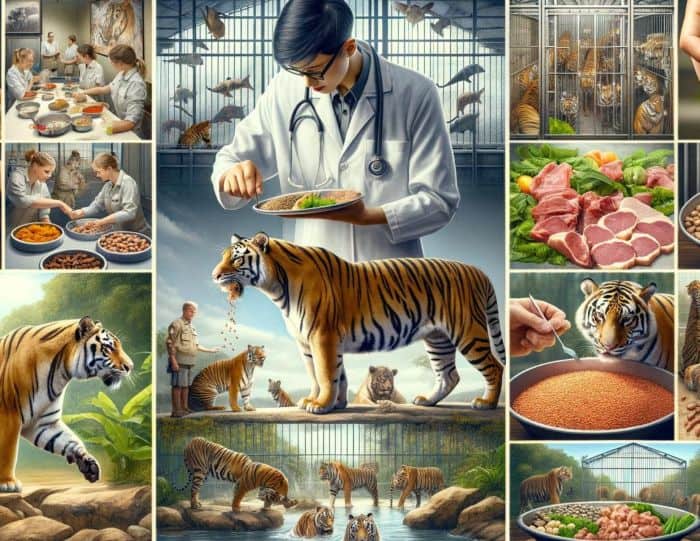

Captive Tiger Diets

Feeding captive tigers involves carefully balancing their nutritional needs to maintain their health and well-being. Unlike their wild counterparts, captive tigers often face a diet that differs significantly in composition and texture. This section explores the various aspects of feeding practices for captive tigers, highlighting the nutritional considerations, common health issues related to diet, and the impact of diet on their overall health.

Common Tiger Feeding Practices

Captive tigers are usually fed a diet that primarily consists of raw meat. This is designed to replicate the nutritional content of their natural diet as closely as possible.

Types of Meat

The most commonly used meats in captive tiger diets include beef, chicken, horse, and sometimes whole prey items. A survey of 32 zoological facilities revealed that commercial raw meat diets were the predominant feeding choice, with horse meat being the most frequently provided protein source.

| Beef | High |

| Chicken | High |

| Horse | Most Common |

| Whole Prey | Occasional |

![]()

Tiger Nutritional Considerations

Captive tigers require a diet that meets their specific nutritional needs, which include adequate protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals. However, providing a diet that matches the complexity of their natural intake can be challenging.

Protein and Fat Content

Raw meat diets for tigers must ensure high protein content and appropriate fat levels. For example, a study evaluating nutrient digestibility in exotic felids, including tigers, found that raw beef-based diets provided the necessary macronutrients efficiently.

| Protein | 80-90% | Raw meat |

| Fat | 5-10% | Raw meat |

| Calcium | 0.6-1% | Bone content, supplements |

| Phosphorus | 0.5-0.8% | Bone content, supplements |

![]()

Health Issues Related to Diet

The diet of captive tigers can significantly impact their gastrointestinal, oral, and overall physical health.

Tiger’s Gastrointestinal Health

A study examining gastrointestinal health in captive tigers indicated that frequent feeding of muscle meat and chicken was associated with increased vomiting and diarrhea. Conversely, including long bones in the diet appeared to reduce these issues.

![]()

Oral Health

Captive tigers fed solely on ground meat diets often suffer from dental issues due to the lack of mechanical chewing required to process their food. This can lead to dental calculus, periodontal disease, and even morphological changes in their cranial structure due to reduced masticatory effort.

![]()

Improving Captive Diets

Efforts to improve the diets of captive tigers focus on mimicking the natural feeding behaviors and nutritional profiles of wild tigers as closely as possible.

Inclusion of Whole Prey

Feeding whole prey items, such as rabbits or deer, can provide nutritional benefits and engage tigers in natural hunting and chewing behaviors, which is beneficial for their psychological health and oral hygiene.

Balancing Nutrients

Supplementing raw meat diets with essential vitamins and minerals is crucial to prevent deficiencies. For instance, ensuring an adequate balance of calcium and phosphorus is vital for bone health, and addressing deficiencies in fatty acids or other essential nutrients is necessary for overall well-being.

![]()

Hunting Success Rates and Strategies of Tigers

As apex predators, tigers rely on their exceptional hunting skills to sustain themselves in the wild. Understanding their hunting success rates and strategies provides valuable insights into their behavior and ecology, essential for effective conservation efforts.

Hunting Success Rates

Tigers’ hunting success rates vary widely depending on prey availability, habitat type, and individual skill. Studies have shown that tigers generally have a success rate of about 5-10% per hunting attempt, which is relatively low but sufficient for survival given their solitary hunting strategy.

Success Rates in Different Habitats

In the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Thailand, a study of eight female radio-collared tigers identified 11 mammalian species from 150 kill sites. The tigers’ hunting success was influenced by the availability of stalking cover, with higher kill rates observed in areas with abundant cover.

| Dense Forest | Higher |

| Open Grasslands | Lower |

![]()

Hunting Strategies

Tigers employ various hunting strategies, primarily ambush and stalking, to capture their prey. These strategies are finely tuned to their physical capabilities and their hunting environments.

Ambush Predation

Ambush predation involves tigers using their stealth to get as close as possible to their prey before launching a sudden attack. This method is highly effective in dense forests and areas with plenty of cover, where tigers can remain hidden until the last moment.

Stalking

In more open habitats, tigers rely on stalking, which involves carefully and quietly approaching their prey. This method requires immense patience and skill, as the tiger must avoid detection until it is within striking distance. The effectiveness of this strategy depends heavily on the tiger’s ability to move silently and blend into the surroundings.

![]()

Factors Influencing Hunting Success

Several factors influence the hunting success of tigers, including prey density, environmental conditions, and the individual skills of the tiger.

Prey Density and Availability

Higher prey density typically results in higher hunting success rates. Tigers can afford to be more selective in areas where prey is abundant and expend less energy on each hunting attempt. Conversely, in areas with low prey density, tigers may have to travel greater distances and make more frequent hunting attempts to secure food.

Environmental Conditions

Environmental conditions such as weather, terrain, and vegetation cover play a significant role in hunting success. Dense vegetation provides cover for ambush tactics, while open areas may favor stalking strategies. Additionally, weather conditions like rain or snow can affect the visibility and scent trails of prey, impacting the tiger’s ability to hunt effectively.

![]()

Case Study: South China Tigers

A study on the hunting performance of captive-born South China tigers reintroduced to the wild assessed their ability to hunt free-ranging prey. The tigers showed a wide range of kill rates, from one blesbuck every 3.14 days to no successful hunts, demonstrating significant individual variation. The presence of stalking cover significantly improved hunting success, highlighting the importance of habitat structure in hunting strategies.

Scavenging Behavior in Tigers

While tigers are predominantly known for their prowess as hunters, they are also opportunistic feeders who engage in scavenging behavior when the opportunity arises. This ability to scavenge can provide crucial dietary supplements, particularly when prey is scarce. Understanding the scavenging habits of tigers offers insights into their ecological adaptability and survival strategies.

Instances of Scavenging

Scavenging by tigers has been documented in various studies, highlighting their adaptability and opportunistic feeding habits. These instances often occur when fresh kills are scarce, and scavenging provides an alternative source of nutrition.

Documented Cases

- Scavenging on Domestic Livestock: Tigers have been observed scavenging on livestock carcasses in regions where human-tiger conflicts are prevalent. This behavior is often a consequence of habitat encroachment and depletion of natural prey, forcing tigers to resort to scavenging to meet their dietary needs.

- Natural Prey: Tigers have also been documented scavenging on the carcasses of naturally deceased animals. This includes large herbivores that succumb to natural causes, disease, or injuries from other predators.

![]()

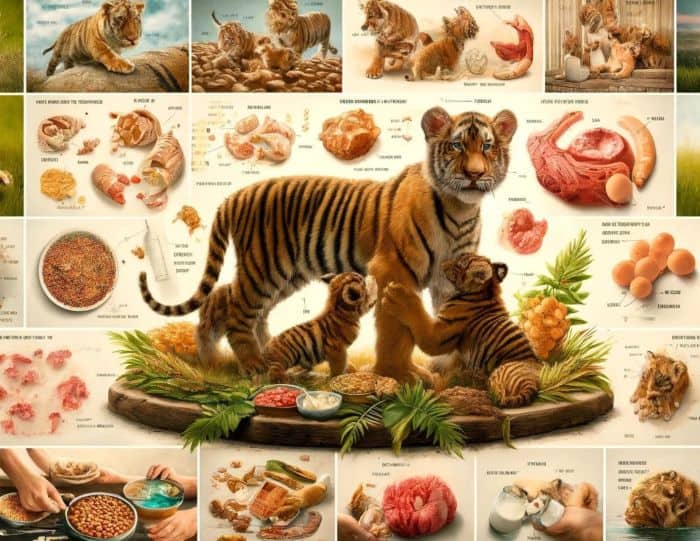

Cub Dietary Needs and Development of Tigers

The dietary needs of tiger cubs are critical for their healthy development and long-term survival. Proper nutrition during the early stages of life ensures robust growth, strengthens the immune system, and prevents developmental disorders. This section explores the nutritional requirements, common dietary practices, and challenges in feeding tiger cubs.

Nutritional Requirements

Tiger cubs require a protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals diet to support their rapid growth and development. Milk from the mother provides the essential nutrients during the initial weeks. Still, as they grow, the introduction of solid food becomes necessary.

Milk and Weaning

During the first few weeks of life, tiger cubs rely exclusively on their mother’s milk, which is rich in essential nutrients. Studies have shown that milk replacers used in captive settings must closely mimic the nutritional profile of natural tiger milk to ensure proper growth and development.

- Protein: Essential for muscle and tissue development.

- Fat: Provides a concentrated source of energy.

- Calcium and Phosphorus: Critical for bone development.

In a study on South China tiger cubs, those fed with KMR (Kitten Milk Replacer) showed normal digestion and growth rates comparable to those naturally nursed by their mothers.

Transition to Solid Food

As tiger cubs grow, their diet transitions from milk to solid food. This process typically begins around the age of 8-10 weeks.

Meat-based Diet

A meat-based diet is introduced gradually, ensuring that the cubs receive a balanced intake of nutrients. The diet usually includes:

- Raw Meat: Beef, chicken, and occasionally whole prey.

- Supplements: Calcium and vitamin supplements to prevent deficiencies.

A case of a tiger cub suffering from nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism due to an unbalanced meat-only diet highlights the importance of dietary supplements. The cub significantly improved after switching to a more balanced diet with added calcium and vitamins.

![]()

Common Health Issues

Improper nutrition can lead to several health issues in tiger cubs, affecting their growth and overall health.

Nutritional Deficiencies

- Rickets and Osteomalacia: Caused by deficiencies in calcium and vitamin D, leading to weak bones and skeletal deformities. This was observed in a study where a Siberian tiger cub developed ataxia and osteodystrophy changes due to an imbalanced diet lacking calcium and vitamins.

- Eye and Skin Conditions: In artificial milk formulas, cataracts, and strabismus have been linked to deficiencies in essential amino acids like taurine, arginine, and histidine. Affected cubs showed significant health improvements after dietary adjustments.

![]()

Case Study: Nutritional Management in Captive Tigers

A comprehensive study on the nutrient and apparent digestibility of the diet of South China Tigers and Bengal Tigers highlighted the importance of balanced nutrition. The study found high protein, fat, and energy digestibility rates, ensuring optimal growth and health.

| Protein | 97 ± 0.7% |

| Fat | 98 ± 1.0% |

| Energy | 97 ± 1.3% |

![]()

Impact of Climate Change and Conservation Efforts on Tiger Diet

Climate change and conservation efforts significantly affect tiger diets by altering their habitats, prey availability, and interaction with human populations. These changes pose challenges and opportunities for tiger conservation, demanding adaptive strategies to ensure survival.

Climate Change Effects on Habitat and Prey

Climate change impacts tiger habitats in various ways, influencing the distribution and abundance of prey species and the availability of suitable hunting grounds.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

Climate change exacerbates habitat loss and fragmentation, which directly affects tiger populations. In the Russian Far East, the Amur tiger faces a dramatic reduction in suitable habitats due to climate change, leading to increased fragmentation and potential population decline.

- Suitable habitats are projected to expand northward but become more fragmented.

- Under severe climate scenarios, tiger populations may decline sharply due to habitat loss.

Changes in Prey Distribution

In regions like the Sundarbans mangrove forest, climate change leads to rising sea levels and increased salinity, negatively affecting prey species’ habitats. This, in turn, impacts tiger diets, forcing them to adapt to new prey or migrate to new areas, increasing human-tiger conflicts.

- Significant decline in suitable habitats for Bengal tigers.

- Increased tiger-human conflicts due to habitat encroachment and prey migration.

![]()

Frequently Asked Questions

What do tigers mainly eat?

Tigers mainly eat large ungulates like deer and wild boar, but they are known to eat a variety of prey, big or small, depending on their geographical location.

How are tigers different from lions when it comes to hunting?

Unlike lions, tigers are solitary hunters. This means they tend to hunt alone, stalking their prey slowly before pouncing on them at high speeds. Tigers can reach up to 40-50 miles per hour in short bursts.

How much food can tigers eat at one time?

Tigers usually eat between 18-20 pounds of meat at one time, but they can consume up to 88 pounds if they are especially hungry.

For tigers mainly, does the size of the prey matter?

How do the hunting habits of male and female tigers vary?

Both male and female tigers are solitary hunters, but males have been known to hunt larger game than females. Female tigers reach their full hunting maturity earlier than males and often hunt smaller game.

Are there tiger subspecies that prefer specific types of prey?

Yes, some tiger subspecies have preferred types of prey. Bengal tigers, for instance, favor ungulates like deer and wild boar. However, they are adaptable hunters and can eat a variety of prey if required.

How has the scarcity of prey affected the tiger population?

As solitary hunters, tigers require significant prey to sustain their populations. Recent declines in their favored prey species due to habitat loss and fragmentation have contributed to a drop in tiger populations, especially in Southeast Asia.

Why are tigers considered efficient hunters?

The tiger is the largest of all big cats in the world. They are solitary, usually hunt alone, and are adapted to bring down prey much larger than themselves. They have a high success rate in hunting due to their strength and agility.

Do tigers eat anything other than meat?

Tigers mainly eat meat and are known as carnivores. This means they eat only meat and do not consume plant material except on some rare situations (where they consume berries or grass to regulate their digestive system).

What makes the tiger such a powerful and successful predator?

Tigers’ solitary nature, their ability to run up to 50 miles per hour, their strength that allows them to take down prey larger than themselves, their sharp retractable claws, and their recognizable black stripes for camouflage make them a formidable and successful predator.

This is great!

I love this text so much and it helped me in school for my school work!

Good luck Michael.