Evolution of Accipitriformes

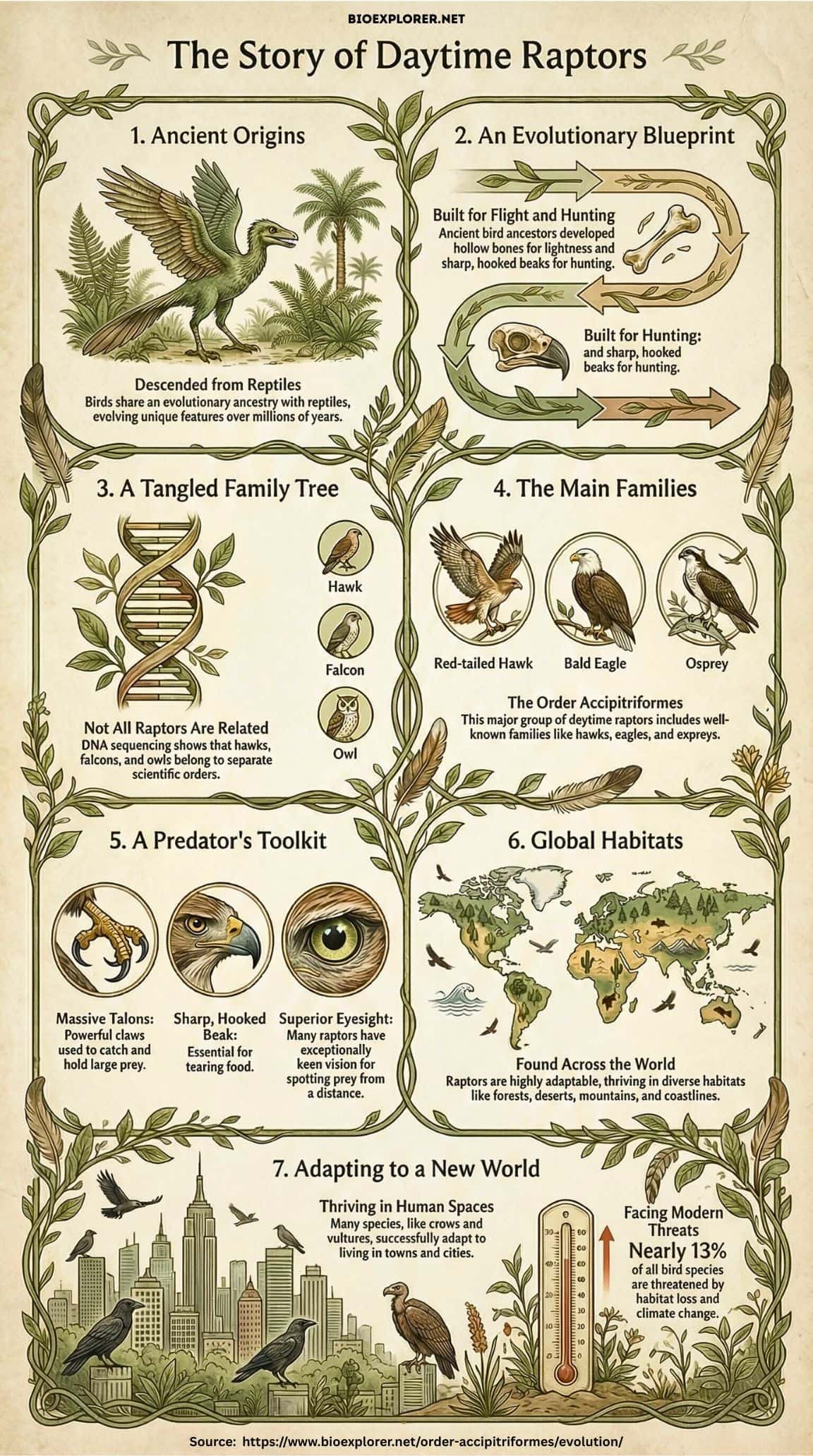

Accipitriformes is the scientific name for a prominent group of types of birds known as diurnal raptors. The term “diurnal” means these birds are active during the day. This group includes well-known aerial predators like hawks, diverse types of eagles, and scavengers like vultures. They are famous for being masters of the sky.

This group is very successful and lives almost everywhere on Earth.

- There are about 260 different species (types) of these birds.

- They live on every continent except for Antarctica.

- They serve as nature's “cleaners” and “hunters”, which helps keep the environment healthy.

Jump to:

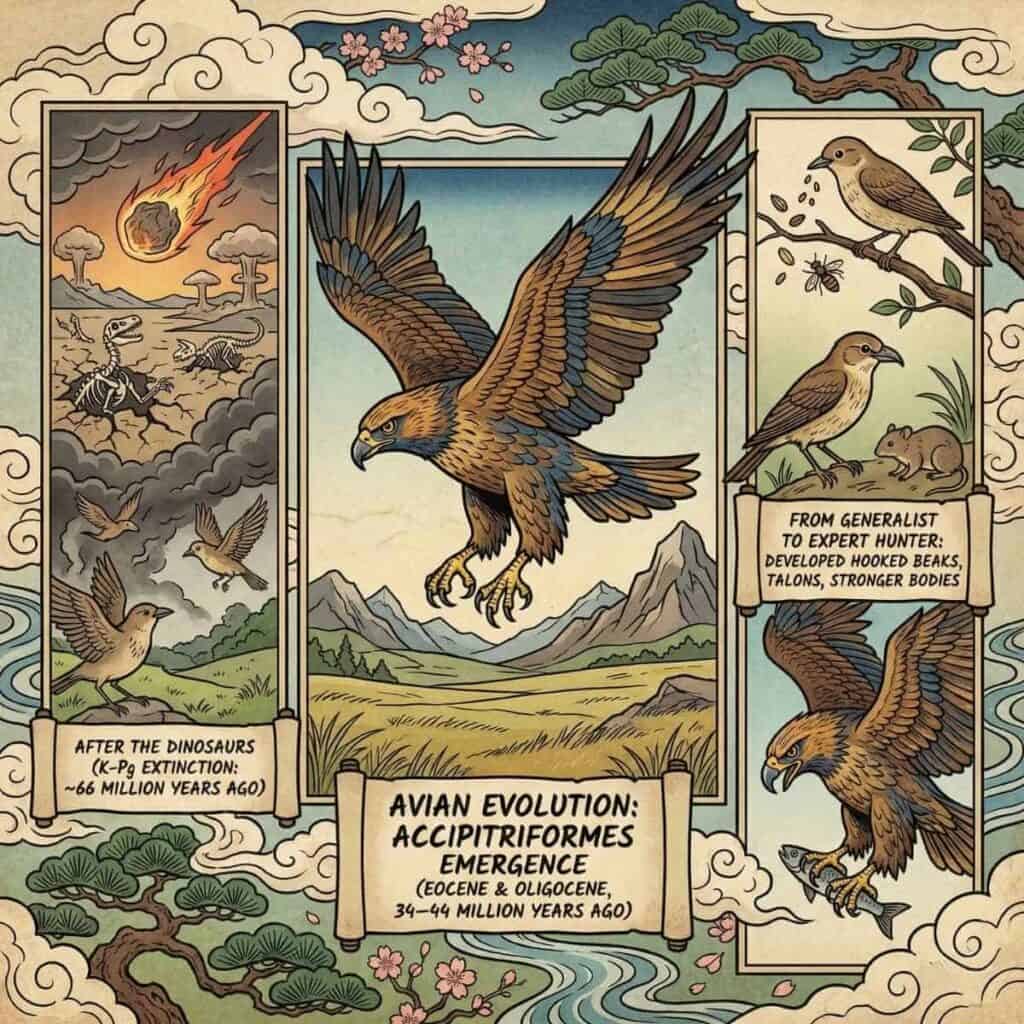

What is Avian Evolution?

Avian evolution is the study of how birds have changed and developed over millions of years. Accipitriformes started to become their own group between 34 and 44 million years ago. This happened during the Eocene and Oligocene periods, which are names for specific chunks of time in Earth’s history. This was long after the flying dinosaurs had already disappeared.

Life After the Dinosaurs

About 66 million years ago, a massive event called the K-Pg extinction wiped out the dinosaurs. While many birds died too, some small birds survived. These survivors eventually led to the modern bird groups we see today.

After the dinosaurs were gone, the world changed:

- Open lands grew, and new types of plants and various types of flowers appeared.

- This created a “job opening” in nature for new hunters.

- Early raptors moved into these roles to catch various types of animals that were becoming more common, including ancestral types of monkeys.

From Eating Everything to Expert Hunting

At first, the ancestors of these birds were generalists. A generalist is an animal that eats many different types of food; understanding the broad range of what do birds eat today provides a glimpse into how their ancestors once relied on seeds or insects. Over time, these birds became specialized predators, focusing their bodies on hunting meat.

To become better hunters, they developed:

- Hooked beaks: Sharp beaks for tearing meat.

- Talons: Strong, sharp claws for grabbing prey.

- Stronger bodies: As environments shifted and various types of trees gave way to open grasslands, they adapted to hunt mammals—including prey like wild rabbits—other birds, and even fish.

By about 30 million years ago, these birds had successfully filled hunting roles all over the world.

Why Their History Matters

Understanding how these birds evolved helps us understand the balance of nature. These birds keep the numbers of rodents and insects from getting too high. Vultures are especially important because they eat dead animals, which stops dangerous diseases from spreading to humans and other animals.

Today, these birds face many threats from humans, such as habitat loss (losing the places where they live) and poisons. By studying their past, we can learn how to protect them today.

While the raptor lineage that led to Accipitriformes was diversifying, other experiments in bird evolution also occurred during the Eocene. One such curious case is the extinct species Aenigmatorhynchus rarus, which possessed a long, enigmatic beak unlike any living birds.

The Timeline of Raptor Evolution and Fossil Clues

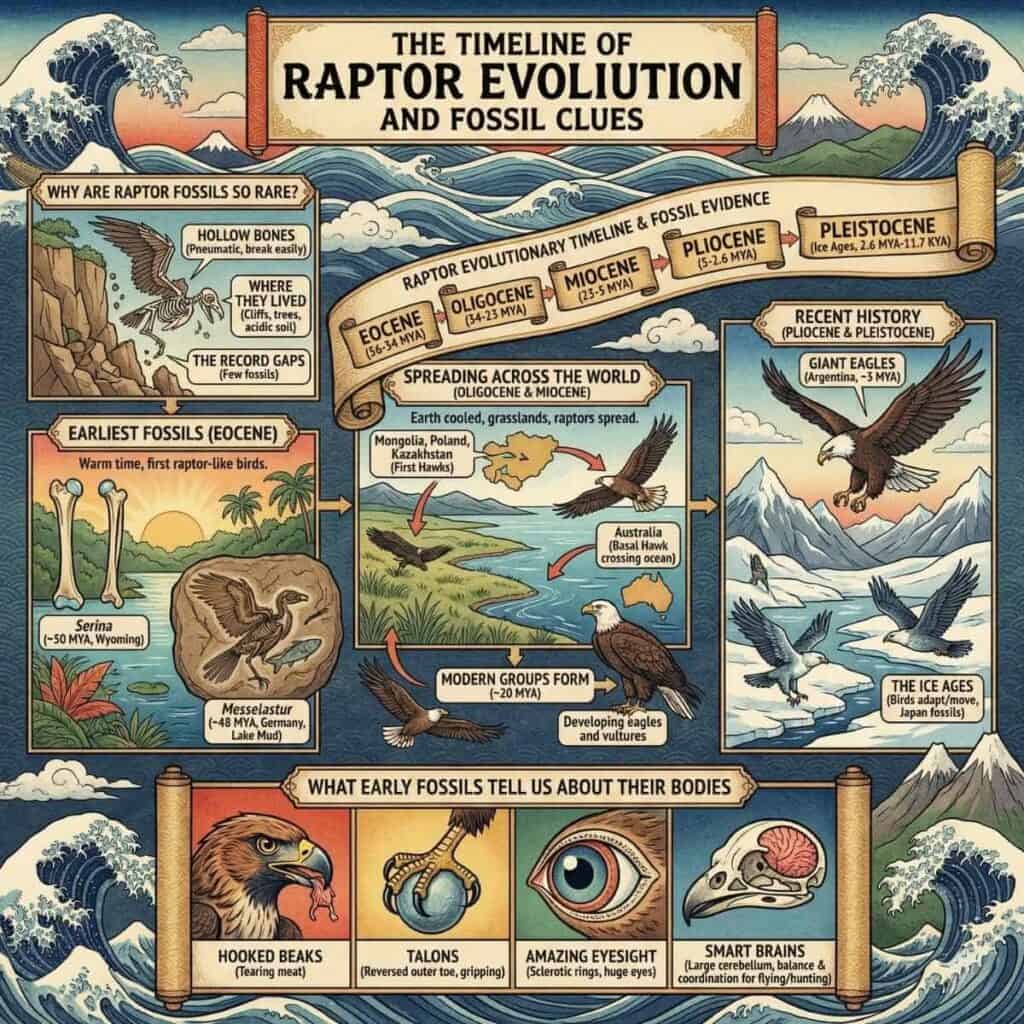

Scientists use fossils and DNA to build a timeline of how these birds changed over millions of years. A timeline is like a long map of history that shows when different groups appeared and moved across the world.

Why ae Raptor Fossils So Rare?

It is very hard to find complete skeletons of ancient raptors. While dinosaur fossil records are often more extensive due to bone density, raptor remains are scarce for several reasons:

Hollow Bones: Raptors have pneumatic bones. This means the bones are hollow and filled with air to make the birds light enough to fly. These thin bones break or rot very easily.

Where They Lived: These birds lived on high cliffs or in trees. When they died, their bones usually fell into soil that was too acidic, which destroyed them before they could turn into fossils.

The Record Gaps: Because of these problems, we have “gaps” in our history where we simply don’t have many fossils to look at.

The Earliest Fossils (The Eocene Period)

- Serina (~50 million years ago): Found in Wyoming, USA. These are some of the oldest leg bones that look like a modern hawk’s legs.

- Messelastur (~48 million years ago): A famous fossil from the Messel Pit in Germany. This site was once a lake in a tropical forest. Because the bird was buried quickly in the lake mud, we can still see its feathers and even what it ate for its last meal! It had a hooked beak and strong feet for grabbing.

Spreading Across the World (Oligocene and Miocene)

- The First Hawks: Fossils from this time have been found in Mongolia, Poland, and Kazakhstan.

- Australia: A “basal” hawk (a very early ancestor) was found in Australia. This shows that raptors were already flying across oceans to reach new lands.

- Modern Groups Form: By about 20 million years ago, almost all the groups we see today—like eagles and vultures—had started to form.

Recent History (Pliocene and Pleistocene)

- Giant Eagles: Fossils from Argentina show large eagles that lived in deserts about 3 million years ago.

- The Ice Ages: During the Pleistocene (the time of the Ice Ages), many birds had to move to warmer areas to survive. Fossils in Japan show how birds adapted to live in colder climates.

What Early Fossils Tell Us About Their Bodies

Even though we don’t have many fossils, the ones we do have show that these birds developed “special tools” very early on:

- Hooked Beaks: Even the oldest fossils had beaks that curved down. This allowed them to tear meat instead of just swallowing seeds.

- Talons: Early raptors had a “reversed” outer toe. This allowed them to grip prey like a person grips a ball.

- Amazing Eyesight: Scientists found sclerotic rings in fossils. These are tiny bones that support the eye. They prove that ancient raptors had huge eyes for seeing movement from far away.

- Smart Brains: By looking at the inside of fossil skulls, scientists found a large cerebellum. This is the part of the brain that controls balance and coordination, which is necessary for flying and hunting.

By the late Eocene, the Accipitriformes lineage split into several major branches that would later become today's hawks, eagles, ospreys, secretarybirds, and vultures.

👉 Explore the families of Accipitriformes

How These Raptors Are Different From Other Birds of Prey

For a long time, people believed that all birds with sharp claws and hooked beaks belonged to the same family. However, modern science has demonstrated that Accipitriformes, such as hawks and eagles, are biologically distinct from other hunters like falcons or various types of owls.

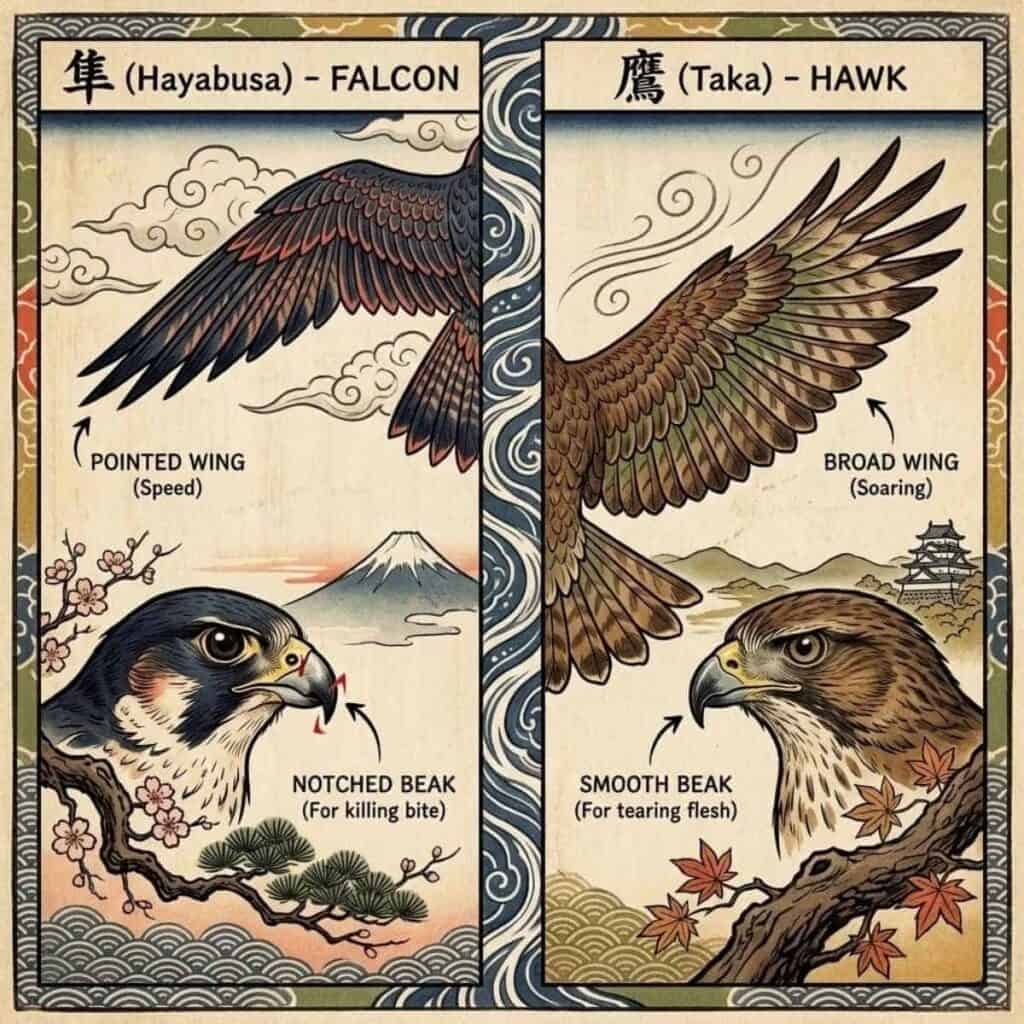

The Big Split: Hawks vs. Falcons

For over 200 years, falcons were grouped with hawks and eagles due to their similar appearance. This is known as convergent evolution, where unrelated animals develop similar “tools” because they lead similar lives. In 2008, DNA studies revealed a surprise: falcons are not hawks. They are actually more closely related to parrots and songbirds—such as the common raven—than to the hawk family.

Why Scientists Changed Their Minds

In 2008, a major study used DNA to look at the “family tree” of birds. DNA is the set of instructions inside every living thing that shows who its true relatives are. The results surprised everyone:

- Falcons are not hawks: Falcons are actually more closely related to parrots and songbirds than they are to hawks.

- Different Hunting Tools: Falcons have a special “notch” on their beak used to snap the necks of their prey. Hawks have smooth beaks.

- Wing Shape: Falcons have pointed wings for high-speed diving. Hawks have broad, wide wings used for soaring and gliding.

Day vs. Night: Hawks vs. Owls

Owls and hawks both hunt other animals, but they split apart on the family tree about 50 to 60 million years ago. One group stayed in the light, and the other moved into the dark.

Different Senses for Different Times

Because they hunt at different times of the day, their bodies changed in different ways:

- Vision: Accipitriformes have eyes built for color and distance in bright light. In contrast, species like the snowy owl or the eastern screech owl have “tube-shaped” eyes optimized for night vision.

- Hearing: Owls rely on a “facial disk” of feathers to catch sound like a satellite dish. Comparing what do owls eat to the diet of hawks shows that while their prey may be similar, their methods of finding it are not.

- Silent Flight: Owls have soft, fringed feathers that allow them to fly silently. Hawks’ feathers make noise when they flap, but they are built for strength and soaring.

The Role of DNA Studies

Scientists use molecular phylogenetics to compare the genetic code of birds. This has helped clarify the family tree, showing that Old World Vultures are actually a type of eagle and New World Vultures are related to hawks. By looking at DNA, scientists can see the true history of these creatures, ensuring that even the most colorful birds are classified correctly despite misleading outward appearances.

These DNA studies have helped “fix” the bird family tree. For example, we now know that:

- Old World Vultures (from Africa and Asia) are actually a type of eagle.

- New World Vultures (from the Americas) are also related to hawks, even though they used to be grouped with storks because of how they look.

By looking at the DNA, scientists can see the true history of these birds, even when their outward appearance might trick us.

The Great Vulture Debate

Scientists have spent a long time arguing about where vultures fit into the bird family tree. This debate shows how science is always changing as we find new information and better ways to study DNA.

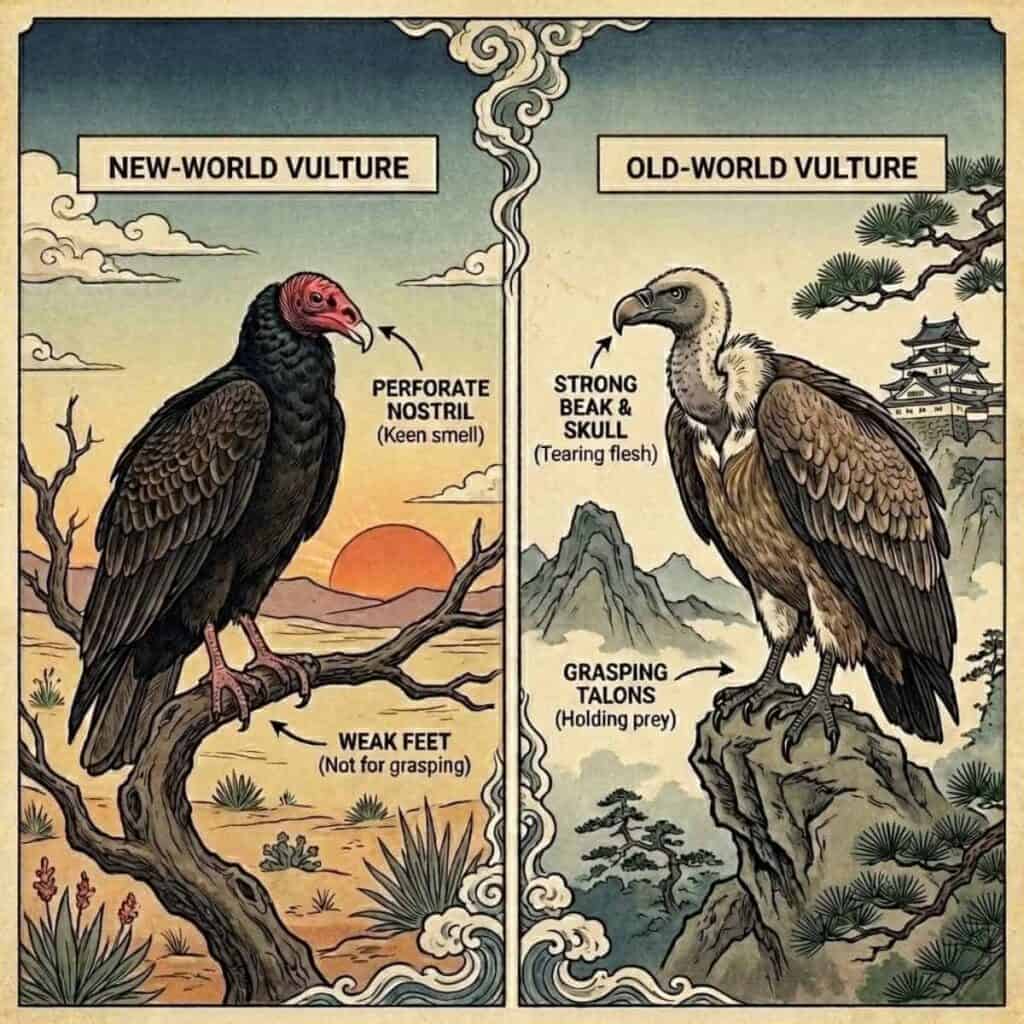

Two Kinds of Vultures

There are two main groups of vultures, and they live in different parts of the world:

- Old World Vultures: These live in Africa, Europe, and Asia. They are part of the hawk and eagle family (Accipitridae).

- New World Vultures: These live in North and South America. They include species like the Turkey Vulture and the California Condor, which are prominent members of the avian landscape alongside other florida birds and texas birds.

The Stork Mystery

In the past, some scientists thought New World vultures were actually related to storks. This is because they have a few things in common with storks that hawks do not have:

- They have long necks.

- They do not have a syrinx, which is the “voice box” birds use to make songs or calls.

- Because of these traits, some experts put them in the stork group, called Ciconiiformes.

What DNA Revealed

In the 1990s and 2008, scientists began looking at the birds’ genes. They discovered that New World vultures are actually much closer to hawks and eagles than to storks.

Even though they look and act like Old World vultures, they split from the main hawk family about 30 to 40 million years ago. Because they have been separate for so long, some scientific lists give them their own special group called Cathartiformes, while others keep them inside the Accipitriformes group.

Why Do Scientists Still Disagree?

Scientists disagree because they have different ways of defining a “group”.

- Some look at the deep history in the DNA and think New World vultures are different enough to be in their own order.

- Others look at how they live and their shared history with hawks and keep them together.

Both sides have good points, and new studies—often highlighted in the latest biochemistry news—may one day settle the argument for good.

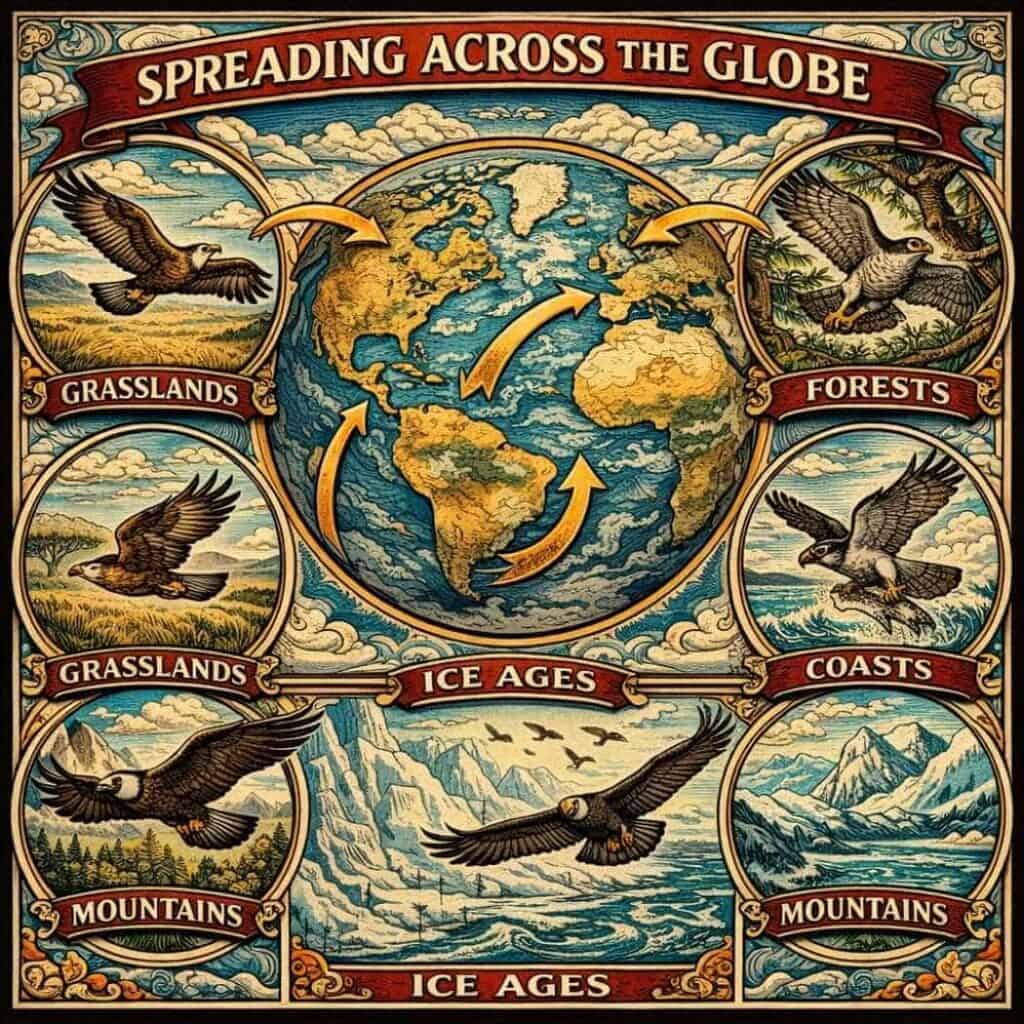

Evolutionary Expansion and Adaptive Radiation

The evolutionary history of Accipitriformes is a classic example of adaptive radiation, where a single ancestral lineage diversified into many forms as it spread into new environments. Over tens of millions of years, these birds expanded across the globe, evolving specialized body plans and hunting styles that allowed them to occupy nearly every major terrestrial habitat.

Origins and Global Dispersal

Fossil and molecular evidence suggests that early members of the hawk and eagle lineage, particularly those within Accipitridae, originated in Africa around 34 million years ago. From this center of origin, Accipitriformes gradually expanded outward as climates cooled and new landscapes emerged.

- Expansion into Eurasia: Around 20 million years ago, the spread of open woodlands and grasslands across Europe and Asia created ideal conditions for soaring predators. This period coincided with the diversification of many hawks and eagles adapted for long-distance flight and open-area hunting.

- Colonization of Australia: Despite its isolation, Australia was reached by ancestral raptors dispersing from Southeast Asia. Once established, these birds evolved into dominant aerial predators within ecosystems that lacked placental mammalian carnivores.

- Arrival in the Americas: Accipitriformes entered North America via the Bering land bridge during periods of lower sea level. Later, the formation of the Isthmus of Panama enabled exchanges between North and South American raptor lineages, accelerating diversification in the Western Hemisphere.

These movements were not single events but occurred in waves, shaped by shifting climates, continental drift, and the rise and fall of land connections.

Morphological Adaptation to New Environments

As Accipitriformes spread, natural selection favored different physical traits depending on local conditions:

- Open Grasslands: This environment favored birds like buzzards and certain eagles that can soar for hours looking for prey in the open.

- Thick Forests: In dark, crowded forests, birds like goshawks developed shorter wings and long tails to help them steer around branches at high speeds. These adaptations are essential for surviving among the many animals that live in rainforests.

- Wetlands and Coasts: Ospreys and sea-eagles stayed near water, developing specialized feet for catching fish. They often share these habitats with other water-specialized species like the anhinga.

- Mountains: Large birds like condors and lammergeiers (bearded vultures) adapted to the thin air and cold temperatures of high mountain peaks.

Why Species Diversity Varies by Region

Raptor diversity is unevenly distributed across the globe, a pattern shaped by long-term evolutionary forces rather than modern conditions alone. Regions with stable climates, complex landscapes, and long periods without glaciation allowed lineages to persist and diversify.

In contrast, areas repeatedly reshaped by ice ages or extreme climatic swings supported fewer long-term evolutionary branches.

Isolation also played a key role. When small populations became separated—on islands or in remote habitats—they often evolved into distinct species through processes such as founder effects and genetic drift.

The Impact of the Ice Ages

During the Pleistocene (the Ice Ages), giant sheets of ice covered much of the northern world, forcing many raptors to move south to survive. When the ice melted, the birds moved back north. These massive shifts in the past are the reason we see certain birds in specific places today, sometimes trapped in small “pockets” separated from their relatives by ancient ice.

Evolution in Motion: Accipitriformes in a Human-Altered World

Evolution within Accipitriformes did not end in the fossil record. Today, human activity has become the dominant selective force shaping the future of these birds, compressing evolutionary pressures that once acted over millennia into mere decades.

Human-Driven Selection Pressures

Rapid environmental changes introduced by humans—urbanization, altered prey bases, and artificial structures—have created new survival challenges and opportunities.

- Some raptors have adapted to novel landscapes, exploiting artificial cliffs, altered prey communities, and new hunting strategies.

- Shifts in diet caused by introduced animals or human waste streams have led to measurable changes in morphology and behavior in certain populations.

- Individuals that survive encounters with hazards such as power infrastructure may pass on traits that improve avoidance or resilience, subtly altering population genetics over time.

These processes represent microevolutionary change occurring within observable timeframes.

Chemical Pressures and Evolutionary Bottlenecks

The widespread use of synthetic chemicals introduced unprecedented selective pressures on raptor populations.

- As apex predators, Accipitriformes are especially vulnerable to biomagnification, where toxins accumulate at higher levels with each step up the food chain.

- Mid-20th-century pesticide use caused catastrophic reproductive failure in several species, creating severe population bottlenecks.

- Although some populations recovered after regulatory changes, modern poisons continue to impose strong selective filters, favoring only the most resilient individuals.

Such bottlenecks reduce genetic diversity, limiting future evolutionary flexibility.

Climate Change and Range Realignment

Global warming is now reshaping habitats that Accipitriformes have occupied for millions of years.

- Many species are shifting their ranges poleward or to higher elevations, tracking suitable climates.

- Changes in seasonal timing can disrupt long-established predator–prey synchrony, reducing breeding success.

- Cold-adapted lineages, especially those in polar or alpine regions, face heightened extinction risk due to habitat loss.

These changes represent ongoing evolutionary stress tests rather than simple ecological displacement.

Genomics and the Future of Raptor Evolution

Modern genomic tools now allow scientists to measure evolutionary health with unprecedented precision. Whole-genome sequencing reveals levels of genetic diversity, inbreeding, and adaptive potential within raptor populations.

- In late 2025 and 2026, researchers used these tools to help save the Philippine Eagle, one of the rarest birds in the world.

- By looking at its DNA, they found that its population has very low “genetic diversity”, which makes it harder for them to fight off new diseases. This information helps conservationists decide which birds should mate to keep the species strong.

Why Their Evolution Still Matters

Accipitriformes are the product of tens of millions of years of evolutionary refinement. Protecting them safeguards more than living species—it preserves the genetic legacy of one of Earth's most successful predatory lineages, ensuring that their evolutionary story can continue in a rapidly changing world.

The story of these birds began in the shadows of the dinosaurs and grew into a global success story. Through fossils, we see their physical changes, and through DNA, we see their true family ties. Whether it is an eagle soaring over a mountain or a vulture cleaning a field, these birds are essential to a healthy planet.

Cite this page

Bio Explorer. (2026, February 1). Evolution of Accipitriformes. https://www.bioexplorer.net/order-accipitriformes/evolution/